One of the most famous knights in tournament fighting during

the 15th century was Jacques de Lalaing. He was born in Douai within the county

of Hainaut, Wallonia. Hainault was located at the borders of France and

Belgium. The Lalaing family was pillars of

the community. Jacques had six siblings: John, the provost of Saint-Lambert’s

Cathedral in Liege; Phillipe, the godson of Philip the Good; Antoine; Yoland

who married the Lord of Brederode and Baron of Holland; Isabeau who married

Pierre of Henin-Lietard Lord of Bossue and Great Baron of Hainaut; and, Jeanne

who married Phillippe Lord of Ducing. Jacques also had a half brother, John,

the Lord of Haubourdin. Jacques happened to be the nephew of Simon de Lalaing.

Simon was Admiral of Flanders from 1436 to 1462. You have to remember, family

and rank meant a great deal in the ancient world. Wait, it still does: guess

things haven’t changed that much.

His general education included training in Latin and

French. Jacques received his military

training under the eye of the Duke of Cleves in the court of Burgundy. In 1436,

The Duke of Burgundy sent Jacques as part of 600 men to service the King of

France under the leadership of Marshall Jean de Villiers de L’Isle-Adam to

Luxembourg. According to chroniclers,

the knight armed with sword and lance struck left and right, accomplishing many

magnificent feats of arms. His bravery and daring brought him fame.

A tournament at Lorraine, in the city of Nancy, in 1445

had Jacques competing before the kings of Sicily, France, and Aragon. Sir

Lalaing was the best. As noted in one biography:

“above all else, he knew the business of arms." Striking

his first opponent squarely in the middle of the shield with his lance, Jacques

"carried both man and horse so rudely to the ground that both the destrier

and the man who rode him were stunned." His next bout was basically the

same way. The third opponent was supposed to be a little tougher: an experienced

jousting knight from Auvergne. On the

third pass, Jacques hit the man on the eye slits, sending sparks flying from

the contact and the Auvergne knight backwards, stunned. He poor man fell off

his horse, unconscious, bleeding from his mouth, ears, and nose. On Lalaing’s

final match, he hit his opponent’s helm in the second pass, sending the

headgear flying roughly 24 feet. Jacques was treated like a celebrity that

night and given the best room and many gifts. The nest day he won eight more

contests. Not bad for a 22 year old.

That year, Jacques started the famous Feats of Arms. This

was a pre-arranged series of ‘friendly’ duels fought in full armor with live

steel. Terms were agreed to in advance, including number of blows. Events could

include jousting with a lance on horseback, sword fighting on horseback, and

fighting on foot with spear or poleaxe, and sword or dagger. Each ‘event’

consisted of three courses, also referred to as ‘Chapters of Arms’. Sometimes

the Feats went on until first blood, yielded, or until one of the men was

carried out on a stretcher.

An Italian knight, Jean de Boniface, from the court of

King Alfonso of Aragon and Sicily, let it be known that he was willing to take

on all comers in a Feat of Arms. Our humble hero, Jacques was willing to take

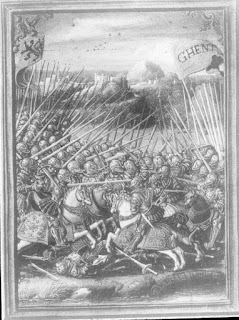

on the braggart. The vent was to occur in Ghent on December 15, 1445. The terms

of the tournament were as follows:

“The combat was to begin on horseback, continuing until

one of the combatants broke 6 lances on the other. The lances were to be of

equal length. The horses were to be separated by a barrier, no more than 5 feet

in height. After this, the combat was to continue on foot in full armor. The

foot combat was to begin with each side hurling spears or "throwing-swords."*

Thereafter, the combat was to continue with poleaxes, swords, and daggers. The

combat would end when one of the combatants touched the ground with his hand,

knee, or body, or when one of them surrendered. Neither party was to affix any

spikes or other "evil device" to his armor, nor was either party to

carry any magical charms designed to influence the outcome.”

The first day Jean broke three lances to Jacque’s two. On

the second day, Jacques decided to switch from a full helm to a half-visored

helmet which would leave the upper part of his face uncovered (his chin and

mouth would be protected). This let him breathe easier but was more dangerous.

During a particular rough spot, Jacques hit Sir Jean hard enough to spin the

knight around. Jacques was able to disarm the man. The referee, the Duke of

Burgundy, stopped the match by throwing down a baton.

Having won the tourney, Jacques travelled seeking more

fights but his fame preceded him. He was denied permission to fight by the

kings of France and Navarre. He did enter the lists against Diego de Guzman,

son of the Grandmaster of the Order of Calatrava by permission of the King of Castile.

As usual, Jacques won. Part of the reason so many monarch might have refused

the knight is that he didn’t travel alone. Jacques had an entourage of that

might have numbered in the hundreds, all fully armed. Of course the rulers

would have been nervous.

For his next

trick, Jacques journeyed to Scotland, Stirling to be exact. His plan was to

fight members of the Douglas clan in front of the King of Scotland. Jacques and five of his men would face off

against six Douglas men on February 25th, 1449 with a crowd estimated at six

thousand in attendance. The men would use spear, poleaxe, sword, and dagger but

no throwing of spears was allowed. Combatants could help one another and the

event would continue until the king declared a halt.

Lalaing’s opponent was James Douglas, the brother of the

earl. Jacques didn’t take long to disarm his man of his spear. James grabbed a

poleaxe, which Jacques took away. James switched to a dagger. He held the

Scotsman off, and discarded his poleaxe. He drew his sword. According the the

record:

"...which was a thin estoc, and grasped the blade

near the point, so he could use it as a dagger, for he had somehow lost his

own." Meanwhile, James had caught hold of his bevor (chin-guard);

attempting to thrust at the unarmored palm of James' hand, Jacques lost his

sword. Now completely disarmed, Jacques caught his opponent with both hands on

his visor, and was in the process of throwing him to the ground when the king

stopped the combat.”

Jacque’s companions had equal success with their opponent’s,

causing the king to stop the event, Lalaing’s next destination was England but

the English king wouldn’t allow the champion to fight.

One Englishman wasn’t intimidated by Jacque’s reputation.

Squire Thomas Que suggested they meet in Bruges, Flanders in 1449. Jacques

agreed. The Duke of Burgundy acted as referee and declared Thomas had to change

his poleaxe as it was not the normal type used in tournaments. Thomas pled his

case to use the weapon long enough that Jacques gave in. Luck was against poor

Jacques for Thomas was able to use the extra long blade to strike a blow:

“As he struck at the Englishman, Jacques had the

ill-fortune to bring his left hand right down on the spike of his opponent’s poleax.

The point entered the underside of his gauntlet, "piercing entirely

through and cutting the nerves and veins, for the spike on the Englishman’s axe

was wondrously large and sharp."

Jacques soldiered

on despite the injury and took Thomas down with a wrestling move that would

have made Hulk Hogan proud. The force of the Que’s impact left his visor buried

in the ground. The Duke stopped the fight.

Jacque’s next feat was a ‘pas d’arms in which for a

designated amount of time he would take on any challenger from November 1rst,

1449 to September 30, 1450. To accomplish the, Jacques would build a pavilion

and hang three shields. The first, a white shield representing fighting with

poleaxes; a violet shield would be for swords; and, a black shield would be for

jousting on horseback. All weapons had to be the same, and he would supply them

but his opponents would have the choice.

Each challenge would continue until a set number of blows specified by

the challenger or until a judge stopped the fight. He named this pas d’arms

(passage of arms), the Passage of the Fountain of Tears because the pavilion

was placed next to a fountain with a fountain with a statue of a weeping woman.

He wore a white surcoat with blue tears. His reason for this? He supposedly

wanted to fight 30 men before his 30th birthday. Lady Luck allowed Jacques to remain

undefeated during this time. He went to Rome where he was admitted to the Order

of the Golden Fleece.

Jacques met a sad end for such a revered man. One of the

factors in the demise of the knight was the development of gunpowder. While

serving Philip the Good, Jacques was struck by cannon fire and killed on July

3, 1453 during the Revolt of Ghent. He

was 32. The death of the knight angered Philip to the point that when he took

Poucques Castle, except for the priests, lepers and children, all occupants

were hanged in retaliation for the killing of Jacques. The King took Jacque’s

body to Lalaing for burial. Later, an epitaph was erected at the Notre Dame

Cathedral.

To read in detail about Jacque’s fights, especially his

Passage, go to:

http://www.thearma.org/essays/Lalaing.htm#.VfQul-_lvIU

The Complete Illustrated History of Knights and Castles

by Charles Phillips

2013 Hermes House

ISBN #978-1-4351-4861-1

Chivalry

by Maurice Keen

1984 Yale University Press

ISBN #0-300-03150-5

Stay safe out there!

Diana,

ReplyDeleteWhat an amazing story!